U.S.S. MAINE

Personal build, A commemorative model for the sailors that lost their lives onboard. Wood and metal, piano wire, jewelry findings

A massive explosion of unknown origin sinks the battleship USS Maine in Cuba’s Havana harbor, killing 260 of the fewer than 400 American crew members aboard.

One of the first American battleships, the Maine weighed more than 6,000 tons and was built at a cost of more than $2 million. Ostensibly on a friendly visit, the Maine had been sent to Cuba to protect the interests of Americans there after a rebellion against Spanish rule broke out in Havana in January.

An official U.S. Naval Court of Inquiry ruled in March that the ship was blown up by a mine, without directly placing the blame on Spain. Much of Congress and a majority of the American public expressed little doubt that Spain was responsible and called for a declaration of war.

Subsequent diplomatic failures to resolve the Maine matter, coupled with United States indignation over Spain’s brutal suppression of the Cuban rebellion and continued losses to American investment, led to the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in April 1898.

Within three months, the United States had decisively defeated Spanish forces on land and sea, and in August an armistice halted the fighting. On December 12, 1898, the Treaty of Paris was signed between the United States and Spain, officially ending the Spanish-American War and granting the United States its first overseas empire with the ceding of such former Spanish possessions as Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines.

In 1976, a team of American naval investigators concluded that the Maineexplosion was likely caused by a fire that ignited its ammunition stocks, not by a Spanish mine or act of sabotage.

Project Details

Client Client Name

Date Date of Completion

Skills Model Design

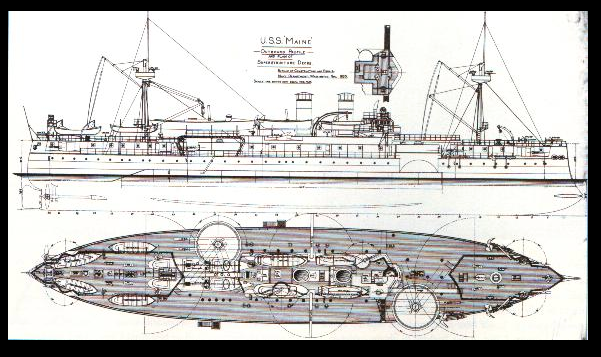

USS Maine (ACR-1), commissioned in 1895, was the first United States Navy ship to be named after the state of Maine.[a][1] Originally classified as an armored cruiser, she was built in response to the Brazilian battleship Riachuelo and the increase of naval forces in Latin America. Maine and her near-sister ship Texasreflected the latest European naval developments, with the layout of her main armament resembling that of the British ironclad Inflexible and comparable Italian ships. Her two gun turrets were staggered en échelon, rather than on the centerline, with the fore gun sponsoned out on the starboard side of the ship and the aft gun on the port side,[2] with cutaways in the superstructure to allow both to fire ahead, astern or across her deck. She dispensed with full masts thanks to the increased reliability of steam engines by the time of her construction.

Despite these advances, Maine was out of date by the time she entered service, due to her protracted construction period and changes in the role of ships of her type, naval tactics and technology.[2] The general use of steel in warship construction precluded the use of ramming without danger to the attacking vessel. The potential for blast damage from firing end on or cross-deck discouraged en échelon gun placement. The changing role of the armored cruiser from a small, heavily armored substitute for the battleship to a fast, lightly armored commerce raider also hastened her obsolescence. Despite these disadvantages, Maine was seen as an advance in American warship design.

Maine is best known for her loss in Havana Harbor on the evening of 15 February 1898. Sent to protect U.S. interests during the Cuban revolt against Spain, she exploded suddenly, without warning, and sank quickly, killing nearly three quarters of her crew. The cause and responsibility for her sinking remained unclear after a board of inquiry investigated. Nevertheless, popular opinion in the U.S., fanned by inflammatory articles printed in the “Yellow Press” by William Randolph Hearstand Joseph Pulitzer, blamed Spain. The phrase, “remember the Maine, to Hell with Spain”, became a rallying cry for action, which came with the Spanish–American War later that year. While the sinking of Mainewas not a direct cause for action, it served as a catalyst, accelerating the approach to a diplomatic impasse between the U.S. and Spain.

The cause of Maine‘s sinking remains a subject of speculation. In 1898, an investigation of the explosion was carried out by a naval board appointed under the McKinley Administration. The consensus of the board was that Maine was destroyed by an external explosion from a mine. However, the validity of this investigation has been challenged. George W. Melville, a chief engineer in the Navy proposed that a more likely cause for the sinking was from a magazine explosion within the vessel. The Navy’s leading ordnance expert, Philip R. Alger took this theory further by suggesting that the magazines were ignited by a spontaneous fire in a coal bunker.[3] The coal used in Maine was bituminous coal, which is known for releasing firedamp, a gas that is prone to spontaneous explosions.[4] There is stronger evidence that the explosion of Maine was caused by an internal coal fire which ignited the magazines. This was a likely cause of the explosion, rather than the initial hypothesis of a mine.

Background

The delivery of the Brazilian battleship Riachuelo in 1883 and the acquisition of other modern armored warships from Europe by Brazil, Argentina and Chile shortly afterwards, alarmed the United States government, as the Brazilian Navywas now the most powerful in the Americas.[5] The chairman of the House Naval Affairs Committee, Hilary A. Herbert, stated to congress: “if all this old navy of ours were drawn up in battle array in mid-ocean and confronted by Riachueloit is doubtful whether a single vessel bearing the American flag would get into port.”[6] These developments helped bring to a head a series of discussions that had been taking place at the Naval Advisory Board since 1881. The board knew at that time that the U.S. Navy could not challenge any major European fleet; at best, it could wear down an opponent’s merchant fleet and hope to make some progress through general attrition there. Moreover, projecting naval force abroad through the use of battleships ran counter to the government policy of isolationism. While some on the board supported a strict policy of commerce raiding, others argued it would be ineffective against the potential threat of enemy battleships stationed near the American coast. The two sides remained essentially deadlocked until Riachuelo manifested.[7]

The board, now confronted with the concrete possibility of hostile warships operating off the American coast, began planning for ships to protect it in 1884. The ships had to fit within existing docks and had to have a shallow draft to enable them to use all the major American ports and bases. Its maximum beam was similarly fixed and the board concluded that at a length of about 300 feet (91 m), the maximum displacement was thus about 7,000 tons. A year later the Bureau of Construction and Repair (C & R) presented two designs to Secretary of the Navy William Collins Whitney, one for a 7,500-ton battleship and one for a 5,000-ton armored cruiser. Whitney decided instead to ask congress for two 6,000-ton warships and they were authorized in August 1886. A design contest was held, asking naval architects to submit designs for the two ships: armored cruiser Maine and battleship Texas. It was specified that Maine had to have a speed of 17 knots(31 km/h; 20 mph), a ram bow, double bottom, and be able to carry two torpedo boats. Her armament was specified as: four 10-inch (254 mm) guns, six 6-inch (152 mm) guns, various light weapons, and four torpedo tubes. It was specifically stated that the main guns “must afford heavy bow and stern fire.”[8] Armor thickness and many details were also defined. Specifications for Texaswere similar, but demanded a main battery of two 12-inch (305 mm) guns and slightly thicker armor.[9]

The winning design for Maine was from Theodore D. Wilson, who served as chief constructor for C & R and was a member on the Naval Advisory Board in 1881. He had designed a number of other warships for the navy.[10] The winning design for Texas was from a British designer, William John, who was working for the Barrow Shipbuilding Company at that time. Both designs resembled the Brazilian battleship Riachuelo, having the main gun turrets sponsoned out over the sides of the ship and echeloned.[11] The winning design for Maine, though conservative and inferior to other contenders, may have received special consideration due to a requirement that one of the two new ships be American–designed.[12]

Congress authorized construction of Maine on 3 August 1886, and her keel was laid down on 17 October 1888, at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. She was the largest vessel built in a U.S. Navy yard up to that time.